Musical archaeology in Washington D.C. :: The Library of Congress yields buried treasure

Archaeology is so hot right now. If you saw the new Indiana Jones movie (or maybe in spite of seeing the new Indiana Jones movie) perhaps you got a little hot under the collar as I often do when I think about trawling through the dust and under the veil of time, looking for things that have been all but forgotten.

Larry Appelbaum is a senior music reference specialist (yes! That’s a real job!) in the Music Division of the Library of Congress, and worked for decades preserving and cataloging their vast stores of audio recorded material. He is also a jazz journalist and radio host — we met when he presented the excellent and random workshop at the conference I was attending.

Larry Appelbaum is a senior music reference specialist (yes! That’s a real job!) in the Music Division of the Library of Congress, and worked for decades preserving and cataloging their vast stores of audio recorded material. He is also a jazz journalist and radio host — we met when he presented the excellent and random workshop at the conference I was attending.

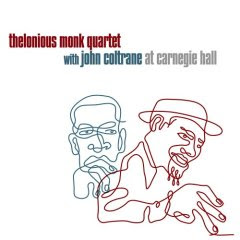

During Appelbaum’s presentation, I became intrigued by a reference he made to a much-fabled lost live recording of Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane that he rediscovered during the course of his work, and ultimately how that resulted in that concert being released on Blue Note in 2005.

The Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall album captures a rare live collaboration between two of the most influential and distinctive musicians in jazz history, in excellent sound quality. It languished for 47 years before Appelbaum and his team came across it in their daily archival work. His heart quickened when he realized what he held in his hands — a recording that had been sought after for years had finally been uncovered in the most unexpected of places.

It’s a great story that seizes the imagination. Appelbaum took some time last Friday afternoon from his offices on Capitol Hill to recount the discovery and the significance for Fuel/Friends.

LARRY APPELBAUM, SENIOR MUSIC REFERENCE SPECIALIST/”JAZZ ARCHAEOLOGIST”

There are a couple of different ways that you discover treasure when it comes to sound recordings. One of them is if you’re looking for it. You search the discographies, you look at all the indices, you look and you read everything you can find, and you take from the very general down to the narrow until you find what you’re looking for. The other way you discover these treasures is — I don’t want to say by accident, but more by chance. This discovery of the Thelonious Monk/John Coltrane tapes was an example of really both of those approaches.

First of all I should say that these recordings represented a sort of musical Holy Grail for jazz scholars. Because despite the fact that Monk and Coltrane are two of the most important and influential and innovative artists, not just in jazz, but in American music, they only worked together for about nine months, and they only made three songs together in the studio, for Riverside (Records).

One of the problems was that Monk was signed to Riverside Records and Coltrane was signed to Prestige — you know how that goes. So they only worked together for those nine months, mostly at a club on the Bowery called The Five Spot. We only had those few songs that everybody clung to and listened to and memorized.

Cut to the end of 2004. I was the supervisor of the Magnetic Recording Laboratory where we do a lot of preservation of recorded sound here at the Library of Congress. We work with lots of different sound collections, one of them is the Voice of America collection. These are about 50,000 open-reel tapes of things recorded primarily in the 1950s and 60s, and sometimes into the 1970s. But when you’ve got 50,000 reels, and you have a number of other important collections, you can’t just devote all your time to one.

So we’d been working through the Voice of America collection for years, and I used to enjoy looking through the queue and seeing what we would be working on for the rest of the week. So one day in late 2004 I saw eight reels titled simply, “Carnegie Hall Jazz: 1957.” That definitely caught my attention — I love jazz, and that’s a good year for jazz, it’s one of my favorite eras. I looked on the back of one of the tape boxes and it’s written in pencil, “T. Monk” with some song titles. That’s it.

I got a little excited because it occurred to me that maybe this was some unpublished Monk. But it was only when I went to actually play the tape that I realized the unmistakable sound of John Coltrane — it’s a sound that’s very near and dear to me. I was really startled by it because I started thinking, “Well, now these are not the studio recordings that we all know from Riverside, this is live. What is this? Carnegie Hall? 1957?”

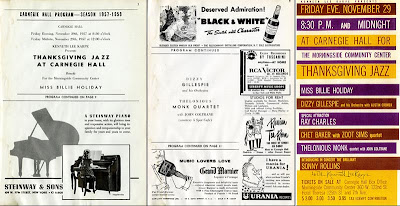

It turns out it is part of a benefit concert from November 29, 1957. Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane was just one of five acts on a bill that also included Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra, Sonny Rollins Trio, Ray Charles, and Zoot Sims with Chet Baker.

It turns out it is part of a benefit concert from November 29, 1957. Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane was just one of five acts on a bill that also included Billie Holiday, Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra, Sonny Rollins Trio, Ray Charles, and Zoot Sims with Chet Baker.

So we had eight reels and it included everything from the 8pm show as well as the midnight show, and all the acts except for Billie Holiday, which still has not been found. I’ve met two people now who were at that concert who both tell me that Billie Holiday was in very bad shape that night. So that leads me to believe that perhaps her show was not recorded, or just that her manager wouldn’t allow it to be released.

We were so lucky, because I don’t think these reels had EVER been played before. They were recorded, wound onto a reel, and just put away in a box for 47 years.

I almost couldn’t believe it. When I heard it, my heart started to race. At that point, I couldn’t quite wrap my head around the fact that this had never been bootlegged, never been circulated. I wondered, is this truly as unique as I think it is? I contacted Lewis Porter, who is the great Coltrane scholar who teaches at Rutgers University. He told me that these had never been circulated, and that scholars had been looking for these tapes for years. No one had ever found them.

In fact, Porter himself had contacted the reference specialists at the Library of Congress, looking for these Monk/Coltrane tapes, and at the time they couldn’t find them because they weren’t properly preserved or cataloged. If he had called and asked, “Do you have Carnegie Hall Jazz 1957?” we could have said yes, but no one had had any idea of what the content was on any of the reels at that point. It’s not enough just to have all of these sound recordings just sitting on a shelf. They were SAFE on a shelf, but we had no idea what they were until we went to transfer them [into digital format to preserve them].

So then I got really excited once I confirmed that yes, this was really unique material, the sound is great — for 1957 it’s a really high quality location recording. We issued a press release announcing the discovery, and [after an initial and unexpected lull] Ben Ratliff, the jazz critic for the New York Times came down and spent the day listening to that recording twice and taking some detailed notes. He wrote a piece that ran on the front page of the New York Times Features section, and that morning the phones started ringing off the hook. It was just unbelievable — every label was calling, asking “How can we get it?”

Now, the Library of Congress does not itself retain any rights to the intellectual property, it all reverts back to the estate of the artist. The attorney of Thelonious Monk’s estate, Alan Bergman, received a listening copy of the recording and took it around to different labels. Working with Monk’s son T.S., it ultimately came out on Blue Note at the end of 2005. I was just so gratified that it sold so well – I mean, you’re used to pop jazz selling well, but to think that a record like that of instrumental jazz that’s not Kenny G, selling half a million copies — that’s unheard of.

Look, I mean, this is why we do what we do! I was really pleased just at the thought that someone maybe bought it for their twelve year old kid who’s just learning music.

I’ve found lots of rare things over the years, things we weren’t even looking for — a jam session with Lester Young during a period when he was in his prime but had been thoroughly undocumented, right before he went into the Army. We’ve been working on preserving all the Newport Jazz Festivals for years, and we have the Newport Folk Festivals as well. We were lucky with the Coltrane/Monk show because it was a really well-made recording, and many other Newport recordings are distorted.

Of course, there’s always more for which we know nothing yet about the content and the significance. We systematically go through things that are in the most danger of degenerating and can’t cherry-pick things out of the collection when other less-stable recordings may be in danger. We’ve been focusing on the ’50s, but what we might find once we get through into the ’60s? I remember one item from our NBC collection from when the Beatles first performed in New York, it was used as backup sound for a news story. Or a 2″ quad video reel I preserved and transferred that was recorded at the Family Dog in San Francisco by NET [National Educational Television] with the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and either Quicksilver or Santana, and then at the end they all jammed together. That was great — not just for the music, but also how you can see the audience and the culture of the moment. And I remember seeing a really nice film of Joni Mitchell once, at a festival in the Midwest where she’s just performing all by herself. Lovely.

Think about it, if I had not been at work that day, we would have still preserved that recording of course — but who would have known what it was? I mean, maybe years later a researcher would walk in the door and look in a database and say, “What’s this?”

Sometimes if all the planets line up just right and you find something with unique content that’s well-done, it can have a profound impact in the music world today, years later. If people can hear something they’ve never heard before, and it moves them, is there anything more important in terms of music and culture? It really says something about who we are.

So yes. To answer your earlier question — yes . . . it’s cool.

Sweet and Lovely (live at Carnegie Hall, 1957) – Thelonious Monk & John Coltrane

BUY: Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall

NOTE: In addition to a Recorded Sound Reference Center online, the Library of Congress also has an American Folklife Listening Room — incidentally staffed by a guy named Todd Harvey who has written a book called The Formative Dylan: Transmission and Stylistic Influences, 1961-1963 that I had fun flipping through as I listened to the tapes of Dylan at Newport in ’63. The main room holds sound recordings that you can listen to and search (I looked through the catalogs of Johnny Cash and Otis Redding). Three hours felt like thirty minutes. If I ever move to DC and no one hears from me for a few months — check there.

[photo credit: New York Times, Stephen Crowley]

Name: Heather Browne

Name: Heather Browne