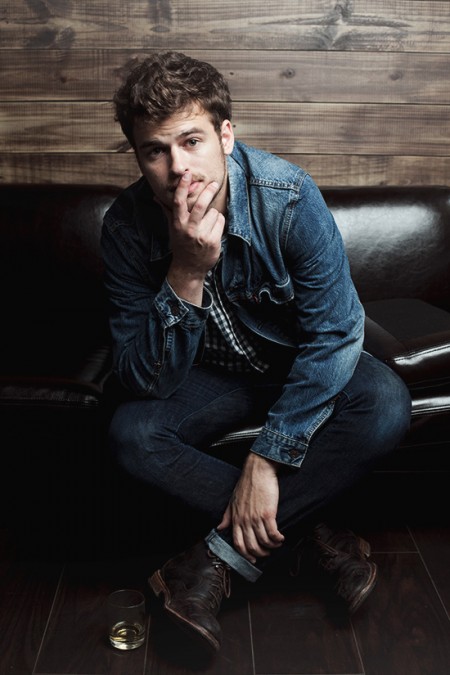

Interview: Winston Yellen of Night Beds

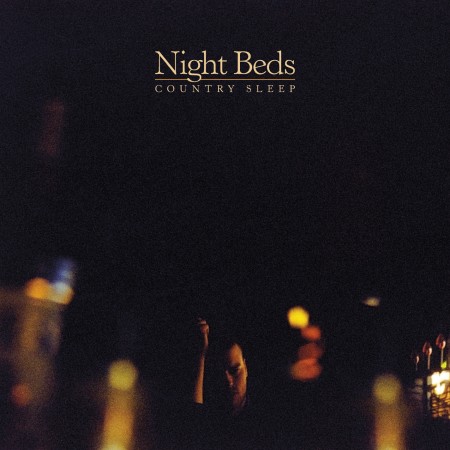

It takes some serious gumption (and a beautiful fragility) to start a record with just your voice for over a minute. Either that or: the song comes to you that way, as the record does, and you record it how it arrived in your consciousness. The first time I clicked on a link on a cold October day to stream the two opening songs on Country Sleep, the debut album from Colorado Springs / Nashville’s Night Beds, I was completely transfixed by whatever beautifully fragile and gumption-filled soul was able to record music like this.

I met Winston Yellen two months later to record our chapel session, and began to learn more about the person who had had this stunning record in him. In the waning hours of 2012, at a remote cabin in the Colorado mountains, Winston and I retreated to a couch in the basement for his first in-depth interview in the U.S.

As the floor above us pulsed with my friends having a New Year’s Eve dance party to the sounds of Frank Ocean, we discussed where these songs come from, the function this art serves, and the beautifully damaged music that inspires him. This is a long interview (and is, of course, edited for clarity, length, and readability). I was very curious, and Winston is my favorite kind of deeply articulate ruminator.

![]() FUEL/FRIENDS INTERVIEW:

FUEL/FRIENDS INTERVIEW:

WINSTON YELLEN OF NIGHT BEDS

DECEMBER 31, 2012

Fuel/Friends: Can you tell me a little about where the songs on Country Sleep come from, and the process by which they came into existence?

Winston Yellen: It’s hard to pinpoint exactly where they come from, but I had an idea in my head that I wanted to make something that was almost …the word that I use is rudimentary — it’s very simple in form. Moving back to Nashville and out to Hendersonville, I got really excited again based on some of the music I was listening to at the time, old country. I got excited again about listening to music that just – it was what it was. I was drawn by that idea of making something completely simple, what people have sometimes written off as rudimentary or sparse and minimal – that was the form I took on, and I think that’s what a lot of old country music was. I kinda made a bastardized record of old country music, that was my attempt, my stab at it.

What was your process in writing this record?

For people who may have liked Night Beds before we made this record, this now is a record that’s very intentional in its form – it’s intentional as an old country record. I wanted to make a simple, stark, minimal record – no fluff because I’d done that in the past, and this record is what it is. As insecure as I am about my voice, I’m just gonna put it out there and put it in the forefront and write my songs on an acoustic guitar or electric guitar. It’s about the song.

I just knew what I needed to do in the moment, and it totally made sense for me and the people involved to make the record that we made. I mean, when you’re living in Johnny Cash’s cabin, you’re gonna make a record…

You lived there?

Yeah…I lived there for five months. He had barns and homes that were all on this plot of land on a hill, and it was very secluded and hidden. He had a main house that he and June occupied for most of the time, I just occupied one of the guest houses that his best friend now owned.

Did you feel that?

Oh yeah, there were definitely some spectres, some weird kind of nights where I was like (in Even If We Try)… “come on Johnny please / won’t you speak to me….” There was a presence there that maybe I just conjured up in myself, but an energy, almost like a struggle within myself to want to make work that is tangible and real. I felt those things, being secluded, and working in this really… weird place. His best friend was living right next door, and coming over and listening to tracks, saying, “Well now. Keep going, I guess.” We were recording through the heat of summer. Felt like a winter record to me, but it’s a summer record.

What was the first song on the album that you recorded?

Ramona. The writing? Faithful Heights because it’s a capella – I wrote that one in my car, I was just driving around. That song, for me, is the weirdest one – it’s so foreign to me, like, “Where did that come from? Who gave that to me?” I don’t know. Then you put it on your iPhone and sing it, or play it really quick, and are like, “Don’t forget that.”

Wow. Do you feel that way about any of the other songs?

I feel blessed to have all of them – I just don’t feel like I should have any of them. Because the fact that I get songs that make me feel good, they kind of just come and I feel the need to be thankful because I just didn’t get them. Someone else should have easily grabbed those by now. That’s how I feel about it. I shouldn’t have gotten those. So yeah, pretty much every song. Yes.

When you’ve written these songs that you feel came to you from “somewhere else,” I mean – do you feel a sense of ownership or catharsis, after they’re recorded down onto the record?

Yeah, and it’s terrifying. For me, I had never gotten that vulnerable with the work I’d done. Some of the stuff I’d done in the past was a little more guarded, a little more ambiguous as to what I was trying to say. I felt very intense about it, but I still felt like I was a little bit removed. But with this record, it kind of did get, at a certain point like I would look around at the other guys in the studio and be like, “We’re gonna have to all talk after we track this. It’s gonna be weird.” There were times in the studio that all of us would be crying. And then listening back in the control room, I’d feel like, “Well that’s not really me. It’s a character.” And it’s like, “yeah, no, of course that’s you.”

I think the writing on this was exciting for me, and also uncomfortably …honest, and it made me a little queasy saying some of this stuff, writing some of these lines. I was hyper self-aware, I just knew – I knew what I was getting myself into as soon as I started doing it, writing this. At the end of the day, yeah, getting that inside of yourself and being willing to spew things that you think are genuine about what’s going on …you hope that if you’re willing to put yourself through that, it might connect with other people. And maybe it will. Maybe it won’t.

I wanted to just say something in a very real, in a very …elementary way. Not a lot of metaphor, not a lot of poetic analogy – just calling a spade a spade, and being direct. There’s times when a songwriter can be ambiguous and abstract, but I didn’t see the point on this record of trying to code it and spice it up and dress it in this way that doesn’t make sense.

And you listen to old country music, that’s what it is – very linear, very direct. They are singing a song, and it is gut-wrenching. When I started hearing those old songs, from country to blues, from the ’30s, all the way into, say, the ’60s, you found stuff that was just so raw, and there was just so much …damage. And they made it so beautiful.

So, you cried in the studio during the making of Country Sleep?

Is this a real question? Do I have to admit this right now? Every song I’ve tracked, I’ve wept. Period. But it can just validate what you’re doing. It’s like, okay now I know why I work a shit job to pay my bills and pay for making this record – If it’s not doing that, you’re not only wasting your time, your wasting other people’s time as well.

At the end of the day, you’re putting out music and asking people to enter in and feel something, and if you’re not feeling something while doing it, I mean – don’t waste people’s time. Don’t show up on their doorstep; leave them alone. I end up having very strong emotions to the recording process, and that’s why you don’t want very many people around when you’re doing it.

Some rare days of recording, there’d just be a perfect storm in all the right ways and we’d put ourselves through it, and we’d walk out and we’d just know that we were …chinking away at the armor.

What musical experiences influenced you, if any, in the way you made this record, or why you made this record?

I heard Robert Johnson, Son House …and I was floored. I was floored. It just really messed me up. I just couldn’t handle the emotion that was going on, couldn’t wrap my head around it; I have a hard time talking about it, to be honest. It really messed me up, how broken they were. These dilapidated creatures that just croaked and moaned and made these songs. Just their circumstances –I mean, being black in the ’30s and ’40s, I remember watching this interview on YouTube with Son House and his eyes were watering, talking about his life. Hearing him start the songs a capella, clapping his hands – “John The Revelator” and “Grinnin’ In Your Face.”

It inspired me enough in that they were so honest. It gave me courage. I’m indebted to that kind of music: I didn’t know that before I heard that. If you don’t feel something when you listen to those voices singing, you’re just not a …not a human being, if your throat doesn’t get swollen up listening to that, to “Sweet Home Chicago,” or “Crossroads.”

What relationship do you see between your art and commerce?

I feel very much ill-equipped to comment on this yet, being so new to it, I don’t know yet. I’m going up there every night playing songs, I don’t know too much about the business, or the culture. I kind of stay out of it. Maybe there will be a time to start getting involved with it. Commerce and art? I don’t know – I think at this point, not to be narcissistic, but I just focus on the work and let other things take care of themselves – I think the best way to service the music and the art and your self, you have to kind of put on the blinders, and put your head down and work, and try to do stuff that’s honest and has an inherent value for yourself, and hopefully for other people. You do it for yourself first, and hope that other people dig it. Yeah, I think I’m gonna have to get there at some point, thinking about the commercial side of things, but that topic does scare me a little bit, for sure.

Country Sleep is such an intensely personal record, and it also sounds …there’s a bravery in there that I hear. What are your goals for this record?

I think I just want to service the work. I felt so strongly the need to make something for myself. But I never believed in myself – I’m never gonna have that belief like, “Hey, bro, you got this.” I just don’t have that, I will never have that. I don’t care what comes; I mean hopefully my label won’t hate me and think I’m the biggest con artist ever, I don’t know. I just put it out there with total fear and trembling, and it came out on the other side, and a few friends were like, “Hey maybe you should pass this around, see if anybody cares,” and I was like “Probably no one will, but I will try,” since I had a little budget left over from the loan I had taken out to make the record, from living on Ramen and peas and rice.

I think any musician has bravery, anyone who goes out on a limb to make the kind of art that they want to make – I mean, you, you’re curating a blog…I think anyone who just puts themselves out there, I just have so much respect for people who take a chance. I love those people. Theatre, writing for a cooking blog, whatever form – submitting yourself to major criticism in order to do the things you want to do. Bravery is rewarding. At the end of the day I think I sleep a little better knowing I’ve been honest and gotten to the heart of the matter, and just gotten it out there in a context I feel is my art.

What’s the motivation? I didn’t have too much – I just knew that I needed to create something at that point in my life, I had been through so much personally. When you’re in that place, you just have to do something. I didn’t know what else to do. (laughs) I had to fail at something else on a grander scale than the menial jobs and what I was failing at then. You kinda have to fail at something grandiose, in order to say, “well, at least I tried.” Put yourself out there, get naked and run around on the highway and not get in trouble. It was my chance to risk myself and give myself the option of being ravenous within the context of art, and work, and see what happened. I feel very blue-collar about music. It’s a blessing to be able to go to Albertson’s and afford to put $80 worth of groceries in my kitchen. So if you’re asking about goals, that’s it: I can do that now.

So …you’ve completed this record and shrink-wrapped it and it’s done, and you tour behind it, you all of a sudden you’re playing with Sharon Van Etten in London. It seems like you’re in this liminal transitional space now between taking this piece of you, externalizing it, and then opening it up and allowing people to interpret and attach their own meaning to it, once you commit it to tape. There’s a certain amount of detachment that goes along with that. I’m curious about your process this year, to go from this intensely personal recording experience, externalizing those songs, and then looking forward in 2013, and in this tour, moving into this realm of transition.

I guess the easy way to say it would be surreal, which I am sure so many people have said in so many of your interviews. But – to do something that was never meant to get beyond the context of your parents and your sister and brothers? To have my sister and brothers talk to me about the record, that was big, that was crazy for me. And then all of a sudden I am in Europe playing songs before Sharon -– I kind of occupied a dream, and I know it sounds cheesy saying that. I still haven’t really wrapped my head around it. I think the fact that people are willing to subject themselves to very personal art that’s not theirs, and they come and they pay money to experience something else and someone else that’s putting themselves out there, for me I really genuinely feel that that’s humbling. I feel a sense of responsibility that I try my best to present the work in the best way possible, because I owe it to people who pay; “I’m gonna come watch your dumbass for ten dollars.” I don’t get it. I won’t get it for awhile.

So, when you and I sit down and talk on New Year’s Eve again next year….

Nothing’s gonna change about how I feel about what I’m doing. Nothing is going to change.

Do you think about the people you wrote the songs about when you’re up on stage?

What do you mean?

Well, I mean I guess if you wrote the songs about other people.

At the end of the day, the songs are about me. No, they’re not about other people. Other people informed the songs, but writing any song is going to correlate back to you. I’m terrified to play music, if that gives you any context. You’re up there playing your songs for people, which you don’t necessarily jones off of. You’re not getting up there saying, “Well I just fucking dig myself-” I don’t. I don’t dig my songs. I …I …They serviced a need that I had. I needed to write those songs and I felt those songs. At this point you get up there and now want to do something that connects – you did it for yourself already and you made the work, now you wanna go reach people and you wanna help people. If people aren’t throwing beer at you, you’re okay.

What did this record fix and what did this record break?

The record didn’t break anything. If you subject yourself to something very intense, and go through the process, which any artist knows in any form, whether it is writing a book or a play, or participate as an actor…. it didn’t break anything. I don’t think it winds up in any of those solidified, exact categories. It’s gonna temporarily fix some things, but it’s gonna keep going and I’m gonna have to address things in the next record, and the next, and probably the next one too.

Just to pour yourself into something, I think there is something to be said for that. Something I say a lot, which I’ll probably continue to say, but this is the first time I’ve said it in an interview and not just to friends, but — I don’t take myself seriously, but I take music really seriously, and I took this record very seriously. With Country Sleep, it was very strict, there was a lot of experimentation but at the same time we were always cutting the fat, striving to make it minimal, because that was the idea and the form, and there’s something very healing about that.

There was something uncomfortable in that, in being so …open. When you’re overexposed, I think it heals something. People go to counseling to be overexposed. I did that on a record. That saved me a lot of checks for therapy. Anybody that does work that’s very personal and overexposed knows – making a record, versus, like spending $100 for thirty minutes with some gal in a suit, that’s how I left it. I’m so broken down when I am in the process of making music, though, not too aware of what’s happening because I am right in it. You know, when you’re looking at a painting and you’re right here….

Ha, yeah, I just got in trouble at the Denver Van Gogh exhibit for standing closer than eighteen inches away from the paintings.

That’s beautiful. Because when you’re so close to art, you’re always in trouble.

Buy Country Sleep, out now on Dead Oceans.

![]() CONTEST: Night Beds plays Denver’s Hi-Dive on Wednesday night. Leave a comment if you would like to win a pair of tickets to the show, Winston’s first official one in his home state of Colorado. I will pick a winner Tuesday, and see you all there.

CONTEST: Night Beds plays Denver’s Hi-Dive on Wednesday night. Leave a comment if you would like to win a pair of tickets to the show, Winston’s first official one in his home state of Colorado. I will pick a winner Tuesday, and see you all there.

[top photo credit Daniel Meigs]

Name: Heather Browne

Name: Heather Browne